Sound Sweeps is an auditory exercise designed to challenge your brain to speed up and sharpen listening accuracy. Only when the brain hears sounds quickly and clearly can it record them accurately. And only when it records them accurately can it recall (remember) them later.

Sound Sweeps is an auditory exercise designed to challenge your brain to speed up and sharpen listening accuracy. Only when the brain hears sounds quickly and clearly can it record them accurately. And only when it records them accurately can it recall (remember) them later.

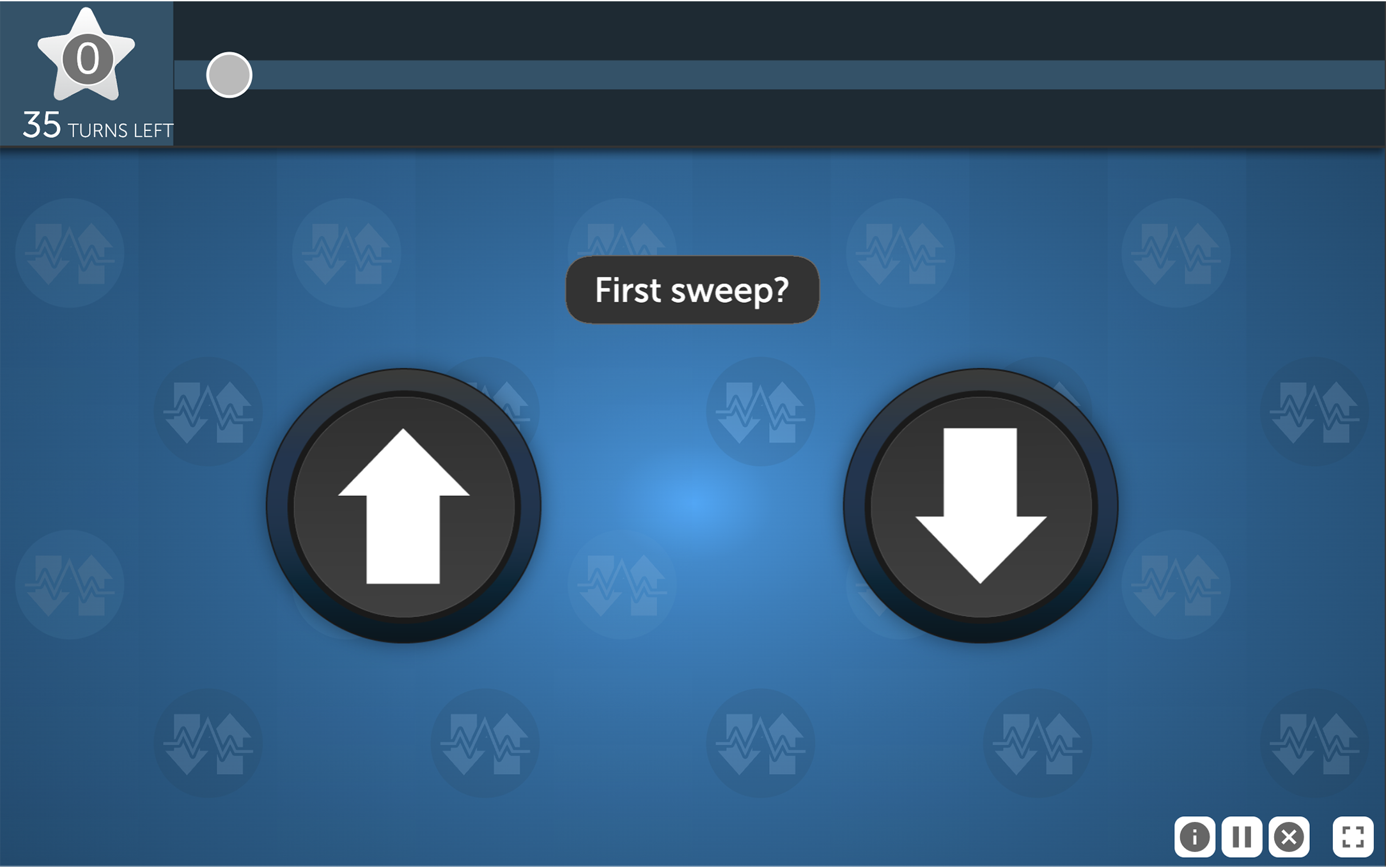

In Sound Sweeps, you have to listen to frequency sweeps—sounds that begin low and rise upward or begin high and fall downward—and identify whether they go up (“weep”) or down (“woop”).

What, you might ask, does this have to do with anything meaningful in real life?

As it turns out, it’s essential our brains can quickly tell frequency sweeps apart in order to understand speech. Although we don’t consciously notice such sweeps when we hear someone talk, many of the sounds common in speech, such as /p/, /d/, /t/, /g/, /k/, and others, are actually made up of a series of sweeps like the ones in the Sound Sweeps exercise. Our brains have to be able to pick these sweeps out in order to identify what a person is saying. For example, one sweep is all that differentiates /g/ from /d/–so it’s all the brain has to tell apart the words “gone” and “dawn,” “big” and “bid,” or “muggy” and “muddy” when it hears them.

These frequency sweeps pass by in mere milliseconds. That’s all the time our brain has to correctly identify them—and the sound, word, and sentence they’re part of. But as we age (and with certain cognitive conditions) our brains tend to slow down. It gets harder to identify these frequency sweeps quickly and accurately…which means we start to have more trouble telling sounds apart.

Often, we can partly adjust for our losses by using context. For example: We might have a hard time hearing the difference between the word bad and the word dad, but in the sentences “My dad is a big guy” and “I’m having a bad day,” we don’t need to be able to distinguish the first sound of the word (/b/ or /d/) precisely. We can intuitively conclude what we must have heard almost immediately, from the context of the sentence and the other sounds in the word. In fact, we probably don’t even notice that we have trouble distinguishing bad from dad.

But there is a consequence for your memory. The brain still recorded the word bad or dad fuzzily—so when you go to retrieve the memory, it’s unclear. It’s surrounded by static.

Over time, your brain’s inability to recognize frequency sweeps quickly can even affect you in the moment of the conversation. As brain connections fade further, the other words in the sentence—those that previously provided the context—may also become harder to recognize. If big guy begins to sound fuzzy—and you are no longer sure if you heard big guy, good buy, big pie, or something else entirely—interpreting the first half of the sentence from context becomes harder. Such distinctions are even more difficult when the speaker is a fast-talking child, a “mumbler,” or someone else who speaks unclearly.

This is when you find yourself saying, “What?” a lot, or starting to just smile and nod when someone speaks to you, unclear of what was said.

The Sound Sweeps exercise can improve your brain’s ability to recognize frequency sweeps quickly and accurately. It does so by asking you to identify sweeps in a variety of frequencies, spaced at different intervals.

Here’s how the sweeps change:

Frequency: As you move through the levels, the sweeps change in frequency. Some will sound high, others low.

Why? Frequency sweeps enable our brain to tell one sound from another—such as a /b/ from a /d/. The sweeps in this exercise mimic frequency sweeps that are part of human speech. Changing the frequency gives you full coverage of the sound frequencies most common in human speech, from 500 to 5000 Hz.

Inter-stimulus Interval (ISI): As you move through the levels, the gap between the two sweeps changes. It’s harder when the gap is shorter.

Why? Sound Sweeps changes ISI to help your brain process sounds separately, even when they occur very close together. As the brain slows, it can experience “backward masking.” Backward masking happens when a second sound comes on the heels of a first sound, causing interference in the brain. It’s still trying to interpret the first sound when the second one comes along. By pushing your brain to hear accurately with shorter ISIs, Sound Sweeps helps speed up the brain to overcome this problem.

These sweeps get faster and faster as you get better at them, so that your brain is always challenged to take it up a level.