Introduction: Piaget and His Ideas

A young child passes a fence with a cow standing nearby and gleefully exclaims: “Dog!” Another child examines a row of seven checkers. When the seven checkers are spread out to form a longer row, the child claims that there are now “more” checkers.

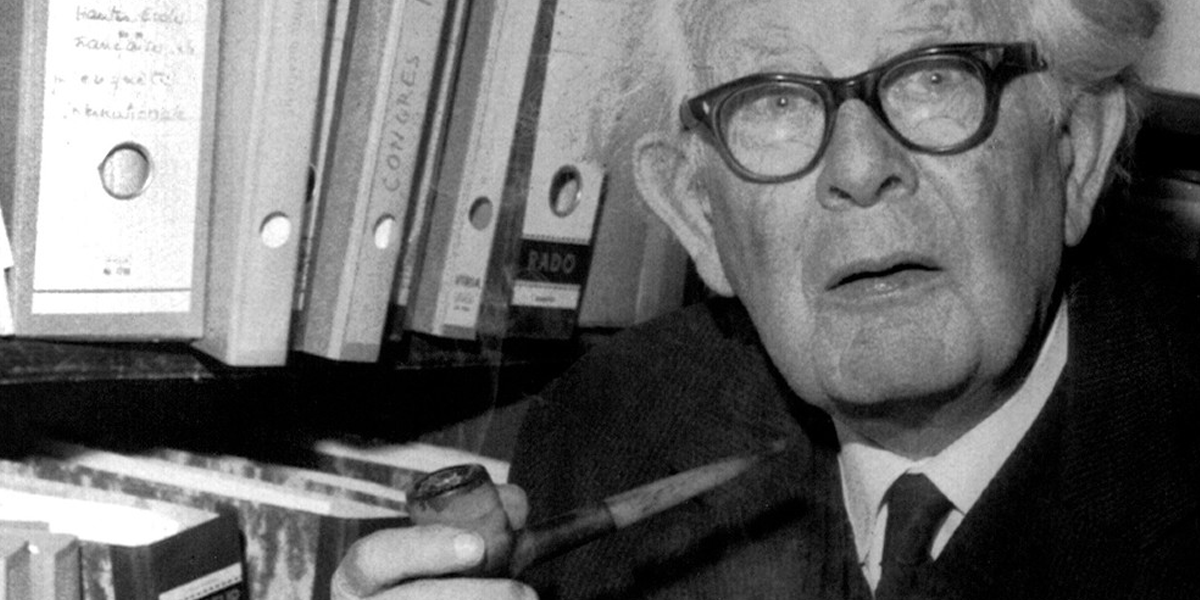

Children have very different ideas about the world than adults do, and many things that adults consider facts are not yet obvious to young children. How do children view the world in their minds? How do they eventually learn that a cow and a dog are not the same? These were the kinds of questions that occupied Jean Piaget (1896-1980), a Swiss scientist who became famous for his theories about the development of intelligence in children.

Of Mollusks and Men

Piaget began his intellectual career early. In 1907, at age ten, he wrote to the director of the natural history museum in his hometown of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, asking for permission to visit the collection after hours. The director, Paul Godet, responded positively, and began teaching Piaget how to classify mollusks. Over the next four years, they spent many afternoons together, examining and labeling mollusk shells. By the time he was a teenager, Piaget was considered an expert in the field.

At the turn of the century, mollusk species were identified almost entirely by the shape, size, and coloring of their shells. A slight variation in a shell’s appearance could give rise to debate as to whether the mollusk constituted a new species, or merely a variety of an existing species. The young Piaget, however, became more interested in behavioral questions that could not always be answered by the shell’s appearance alone: how does a mollusk adapt to change? What, for example, does a mollusk need to “know” in order to adjust to a habitat with stronger water currents?

These kinds of questions formed the basis of Piaget’s lifetime intellectual endeavor: to study the formation of knowledge. After receiving his doctorate in biology, Piaget decided to take up these questions in a different context, and began working with children in an elementary school in Paris. He became fascinated by the answers they gave on intelligence tests, especially the “wrong” answers that revealed something about the child’s construction of the world. He realized that concepts which are self-evident to adults — that a piece of modeling clay retains the same mass and volume, for example, even if we re-shape it — are not at all obvious to young children, but are learned over time.

After Paris, Piaget returned to Switzerland where he began his extensive studies of children’s intellectual development. But his biological background remained with him. As he told interviewer Jean-Claude Bringuier in 1969, “I am convinced that there is no sort of boundary between the living and the mental or between the biological and the psychological. From the moment an organism takes account of a previous experience and adapts to a new situation, that very much resembles psychology.”

The Child’s Conception of the World

According to Piaget, the starting point of a child’s intellectual growth is his or her own action. As the child actively engages with the people and objects around her, she begins to form mental constructs about what the world is like. A newborn, for example, will suck indiscriminately on a nipple, a finger, or a blanket, until she realizes that nipples produce milk while other objects do not. It’s the child’s own experimentation that leads her to this conclusion, and to the creation of a “schema”.

A schema is the mental construct from which behavior flows. A young child, for example, may construct a schema for “cat”: the furry pet who sleeps on the family couch is a cat. When the child sees a two-dimensional picture of a furry animal in a storybook, he may also call it a cat, indicating that he has assimilated the picture into his cat schema. Piaget claimed that this process of assimilating new information into an existing schema was similar to the biological process of digestion: an organism eats food, digests it, and converts it into a usable form.

Of course, the animal in the storybook might not look like the cat at home, in which case the child may have to reconsider. Is it a new kind of cat? If so, the child may modify his existing cat schema to accommodate the picture. Or is it a different animal altogether? In this case the child may create a new mental structure, such as a mouse schema, to accommodate the picture.

As children grow older, their schemas become more numerous and differentiated. Piaget was especially interested in schemas concerning the child’s understanding of objects and their properties, such as shape and size. He observed, for example, that an eight month old baby will flip a feeding bottle if it is presented to her upside down, but a younger baby typically will not, because she does not yet attribute a fixed shape to the bottle. A typical twelve-month old baby will try to search for a toy that is hidden, indicating that she knows the toy exists even when she cannot see it. And a two-year old will begin to understand how objects behave even before she has any direct experience with them, as when Piaget’s daughter Lucienne reversed the direction of her new doll carriage by simply pushing it from the opposite side.

With older children, Piaget conducted experiments that examined how children acquire knowledge of more detailed object properties, such as volume and mass. For example, he would present a child with two glass containers of the same size and shape, each containing the same amount of water, and ask the child to compare the amount of water in each container. Piaget would then take one container and pour its contents into a taller, thinner container, again asking the child to compare the amount of water in each. Until around age seven, most children respond that the taller, thinner container now has more water than the other container — they do not understand that the water conserves its volume. In other experiments with rows of checkers, Piaget demonstrated how young children tend to fixate on a particular property of an object (such as the length of a row of checkers) while ignoring other properties (such as the number of checkers in the row).

“Read Nothing in Your Own field”

From the 1920s until his death in 1980, Piaget worked tirelessly, publishing dozens of books and hundreds of articles. At the International Center for Genetic Epistemology in Geneva, he assembled a large team of scholars from many different fields, such as biology, physics, logic, and history. Piaget believed that an interdisciplinary approach was the best, indeed the only, way to explore knowledge. When working on a new problem, he avoided reading scientific literature directly related to it, for fear that it might stifle his creativity. Instead, he focused on the literature in related fields, and often asked colleagues to give mini-lectures on how their particular specialty related to epistemological questions.

Piaget also preferred a descriptive, rather than a statistical approach to research, and some scientists think this is why his ideas were slow to be adopted in the United States. He kept extensive notes on each of his three children, recording many of their first movements as newborns and conducting simple experiments with them as they grew older. For example, he recorded the following observation when his son Laurent was one month old:

First he makes vigorous sucking-like movements, then his right hand may be seen approaching his mouth, touching his lower lip and finally being grasped. But as only the index finger was grasped, the hand fell out again. Shortly afterward it returned. This time the thumb was in the mouth while the index finger was placed between the gums and the upper lip. The hand then moves 5 centimeters away from the mouth only to reenter it; now the thumb is grasped and the other fingers remain outside.

It may come as no surprise that even dedicated readers have difficulty making it through all of Piaget’s writings. Some of his notes are as detailed (but not as evocative), as Marcel Proust’s recollections in the multi-volume novel Remembrance of Things Past, and it seems that Piaget admired the novelist. He told an interviewer: “I can’t tell you how often I’ve read all the way through Proust… Why, it’s as great stuff as epistemology!”

For laboratory experiments, Piaget and his team devised questioning procedures that they used to begin conversations with children. Each conversation changed course depending upon the response of the child, and Piaget himself freely admitted that he rarely exposed his subjects to consistent experimental conditions. Nor did he work with many children outside the cultural milieu of Geneva. Since he believed that the general course of intellectual development is the same for all people, and that the truly interesting information lies in the detail of a child’s response, Piaget did not feel it was necessary to work with large sample sizes.

Piaget’s Legacy

Piaget’s work has been widely cited among both scientists and educators. There has been no consensus, however, as to the best application of his findings, and Piaget did not usually comment on such practical issues as curricula. He preferred to leave these questions to teachers. In fact, Piaget was not altogether interested in the role of education, and preferred to focus on mathematical and scientific concepts that children form as their intelligence develops naturally. Some of these concepts are quite sophisticated, even in a child who has not yet begun formal education, as a physicist from Piaget’s lab in Geneva explained: “What is done by the child of four, five, or six can often be described in the same words that describe what is done by contemporary physicists. The words are the same. They try to bring order out of chaos, and they use the same operations, the same classifications, to such a degree that it can seem — I won’t say humiliating — but shocking.”