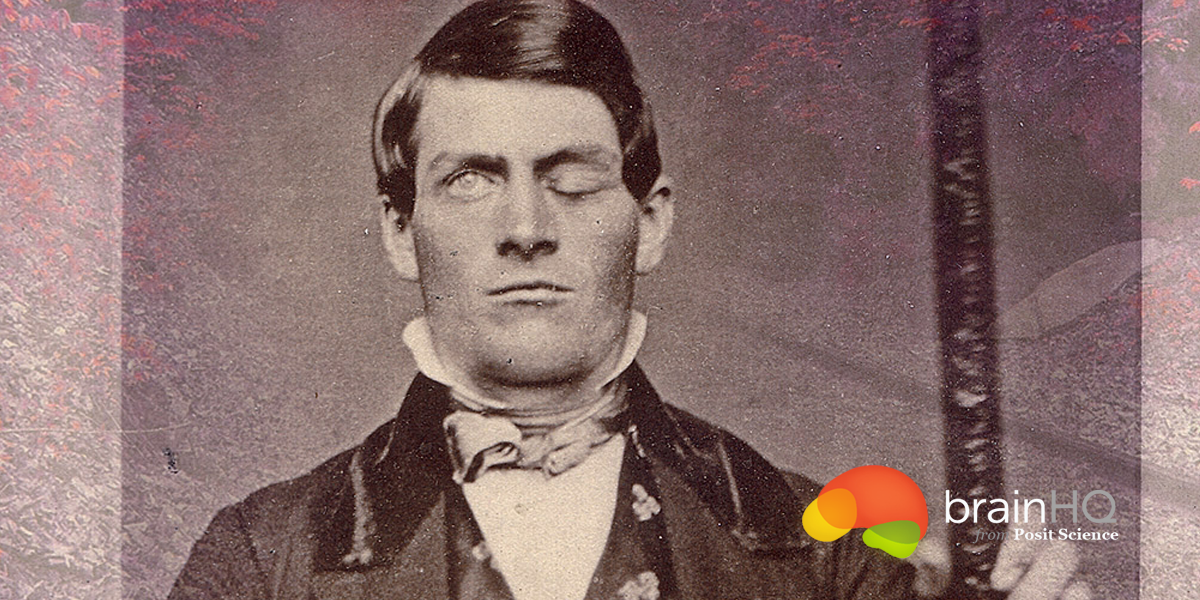

Phineas Gage began the day of September 13, 1848 as a man remarkable only to those who knew him personally. He worked as the foreman of a railway construction gang in Vermont, where his group was preparing the bed for the Rutland and Burlington Rail Road. At just twenty-six years old, Gage was already a success story. Full of vim and vigor, he was well liked by the men in his charge, and his superiors were impressed with his skill at handling dangerous explosives. Gage had a combination of intelligence and athletic ability that made him perfect for the task of clearing rock from the path of the coming railroad. As his bosses noted, he was “the most efficient and capable man” in their employ.

The essence of Gage’s job was to remove large sections of rock by shattering it from the inside out. First, a hole was drilled deep into the boulder, and then it was filled halfway with explosive powder. Next, a fuse was inserted, and sand was poured on top of the fuse. What followed was the riskiest part of the whole enterprise. To direct the explosion into the rock instead of back out the hole, the sand had to be “tamped down” with an iron rod. Gage, who was a master at tamping, had his own rod manufactured to his specifications. It was 3 feet 7 inches long, weighed 13 1/2 pounds, and was 1 1/4 inches in diameter at one end, tapering over a distance of about 1 foot to a diameter of 1/4 inch at the other. By all accounts, Gage had used the iron hundreds of times without incident, and there was no reason to think the afternoon of September 13th would prove any different. But his lucky streak ended abruptly at four-thirty on that late summer day.

Gage had drilled a hole into the rock and filled it with powder, indicating to the man helping him that it was time to put in the sand. At that point, someone called to Gage and he must have become distracted. He failed to notice that his colleague had not yet added the sand to the hole and began tamping directly onto the explosive powder. Almost immediately the sparks struck fire in the hole and the charge blew up in Gage’s face. The force of the explosion drove his three-foot long iron rod at high speed into Gage’s left cheekbone, through his skull and out the top of his head. It landed nearly 300 feet away.

Amazingly, Gage survived the terrible blow. Witnesses reported that while he was thrown to the ground and exhibited a few convulsions, he was alert and rational within a few minutes after the accident. His men picked him up and took him by ox cart to a nearby hotel, where they summoned one of the town’s physicians, Dr. John Harlow. One of Harlow’s assistants, Dr. Edward Williams, responded to the call, and he later wrote of the scene:

“He at that time was sitting in a chair upon the piazza of Mr. Adams’ hotel, in Cavendish. When I drop up, he said, ‘Doctor, here is business for you.’ I first noticed the wound upon the head before I alighted from my carriage, the pulsations of the brain being very distinct; there was also an appearance which, before I examined the head, I could not account for: the top of the head appeared somewhat like an inverted funnel; this was owing, I discovered, to the bone being fracture about the opening for a distance of about two inches in every direction.”

Gage was still conscious at the time of the exam and able to answer questions about his accident, but his survival was not yet assured. Dr. Harlow did not have the benefit of antibiotics in treating Gage. However, he was knowledgeable enough about infection to understand its life-threatening risk and kept vigilant watch over Gage’s wound, cleaning and draining it regularly. Gage’s youth and previous health proved stronger forces than the infection, and within two months he was cured.

Or was he?

No Longer Gage

Miraculously, Gage suffered no motor or speech impairments as a result of his traumatic brain injury. His memory was intact, and he gradually regained his physical strength. Dr. Harlow initially concluded that Gage was fortunate because his injury involved an expendable part of the brain. But in fact something was lost to Gage that terrible afternoon. His personality underwent a dramatic shift, changing his disposition to such a degree that his friends barely recognized him. “Gage,” they said, “was no longer Gage.”

Once a polite and caring person, Gage became prone to selfish behavior and bursts of profanity. Dr. Harlow said it was if Gage lost the balance between “his intellectual faculty and animal propensities.” He had no respect for social graces and often lied about his accomplishments. Previously energetic and focused, he was now erratic and unreliable. He had trouble forming and executing plans. There was no evidence of forethought in his actions, and he often made choices against his best interests. No amount of pleading or lecturing from Dr. Harlow made any difference to Gage. Eventually, his capricious and offensive behavior cost him his job with the railroad contractors. It was not any physical disability that prevented Gage from working; it was his character.

It took years for Dr. Harlow to admit that while his most famous patient survived, he never really recovered. By 1868, he was ready to accept the surprising message inherent in Gage’s tragic story, namely that observing social convention, behaving ethically, and making good life choices requires knowledge of strategies and rules that are separate from those necessary for basic memory, motor and speech processing. Even more startling, it appeared as though there are systems in the brain dedicated primarily to reasoning. The search to find these specific brain areas has stretched from Gage’s time right up to the present day. Scientists now have a pretty good idea of what happened to Gage’s brain, thanks to clues from animal studies, patients with unfortunate brain damage and some unorthodox brain surgeries performed on psychiatric patients during the middle of the twentieth century. Even Gage himself provided some answers 125 years after his death, when Hanna Damasio reconstructed his terrible accident with the aid of computer technology.

A Locus for Personality?

When Gage died in 1861 there was no autopsy performed, so no one was able to verify the exact brain regions damaged in his accident. Fortunately for later researchers, Dr. Harlow had Gage’s body exhumed in 1866, at which point the skull and the tamping iron he was buried with went to the Warren Medical Museum of Harvard Medical School, where they have remained ever since. It was obvious from looking at Gage’s skull that the rod had pierced through the very front part of the brain, but at the time no one knew very much about the sort of processing that occurs in this region. Gage’s accident seemed to suggest that the prefrontal cortex controls decision making, especially in social situations, and has a great deal of influence on temperament. Later evidence from other patients with brain damage supported this idea.

Some of the first indications that Gage’s personality shift was not just a fluke came from other people with injuries to the prefrontal cortex. In the years that followed Dr. Harlow’s 1868 report, other physicians began noting patients who underwent radical personality changes similar to Gage’s after suffering damage to the frontal lobe. They had trouble holding a job, had little respect for social convention, and seemed indifferent to those around them. They formulated plans but could never seem to carry them out. They made life choices that were clearly against their own best interests. In nearly all cases, an autopsy of these individuals revealed severe damage to the prefrontal cortices. Further evidence linking personality changes to prefrontal lobe damage came from a Yale Study on chimpanzees. The researchers had two monkeys who were especially difficult to work with because they frustrated easily and tended to lash out in retaliation. Researchers then performed surgeries on these monkeys that damaged their frontal lobes. After the surgery, both chimpanzees were docile and cooperative. When the results of this study came to light at a medical conference in 1935, scientists wondered if this kind of surgery could produce similar results in humans. This hypothesis led to an infamous kind of psychiatric surgery performed during the 1940s and 50s known as the frontal lobotomy. Patients with various kinds of psychosis underwent surgery to purposefully damage their frontal lobes in an effort to cure them of their illnesses. Interestingly, the surgery did seem help some people, especially those with terrible anxiety, but the overall emotional blunting proved no great cure. It did, however, strengthen the link between the social aspects of personality and the prefrontal cortex.

These days, scientists know a lot more about the anatomy of the prefrontal cortex. It is an association area of the brain, which means that it integrates many processes from other brain regions, including those specialized for memory and emotion. Damage to the prefrontal cortex does not disrupt the basic function of sensory, memory or emotional systems; it disrupts a person’s ability to synthesize these systems and produce organized social behavior. Thus, it was not surprising when Hanna Damasio’s 1994 video reconstruction of Gage’s brain revealed he had damage to the inner part of both prefrontal cortices. Nearly 150 years after Gage’s accident, researchers finally zeroed in on the brain regions responsible for his strange personality change.

A Question of Timing

Phineas Gage’s timing was off on the afternoon of September 13, 1848. If he had waited a few more seconds until the sand was poured into the hole, his tamping iron would not have triggered the explosion that caused his terrible injury. He could have continued his career as a successful foreman instead of winding up as display in P.T. Barnum’s museum for freaks of nature. Unable to hold a job or maintain a solid personal relationship, Gage drifted to San Fransisco, where he died of a seizure disorder at the age of thirty-eight.

But for neuroscientists, the timing of Gage’s accident was fortuitous. Scientists were becoming extremely interested in the mind/brain connection, and their knowledge of anatomy was expanding rapidly. Gage’s case was among the first indications that the brain is not just specialized for walking, talking and the like, but also contains regions tailored for more complex behaviors such as reasoning, adapting to social convention and planning future events. This insight still drives many researchers today, as they build on the knowledge gained from Gage’s fateful accident.

As much as Gage’s story hinges on timing, it is also a timeless one. Terrible in its description and haunting in its tragedy, Gage’s story will be forever remembered as a peek into how three pounds of gray matter somehow combine to make us uniquely human, and each human unique.